The Most Notable Medical Findings of 2016

“At

least you have your research world, where there are facts,” a

journalist friend told me recently. He was referring, of course, to the

sharp Orwellian turn that our public discourse has taken in the past

year, when practically anyone who traffics in truth—scientists,

reporters, intelligence experts, cyber-security specialists—has been

dismissed by our President-elect as a liar or a shill. My friend was

right: research has indeed provided a respite from the maddening media

conversation, a chance to challenge the assumptions and biases of

medical science and public health not with bluster and noise but with

rigorous experimentation. It was with this in mind that I selected the

notable findings of 2016. Welcome to the sanctuary.

Exculpating Patient Zero

The

history of medicine, like the history of the justice system, is filled

with cases of wrongful conviction. In the Middle Ages, for instance,

Jews were accused of having orchestrated an outbreak of the Black Death

by poisoning town wells; there were pogroms across Europe. In our era,

the epidemic was AIDS and the scapegoat was Gaëtan Dugas,

a gay flight attendant from Quebec. He featured prominently in “And the

Band Played On,” Randy Shilts’s best-selling book from 1987, in which

Dugas was identified as Patient Zero—that is, the person responsible for

bringing the disease to the continental United States. Shilts’s

characterization of Dugas as a “suave Quebecois” who travelled the world

having high-risk sex was seized upon by homophobes as proof that the

wages of sin is death. As a result, the Reagan Administration was

shamefully passive in the face of an explosive epidemic, and some

medical researchers, similarly colored by prejudice, initially dubbed

the disease GRID, for “gay-related immune deficiency,”

despite evidence of infection among straight immigrants from the

Caribbean and hemophiliacs who had received transfusions of tainted

blood.

Dugas succumbed to an AIDS-related cancer in 1984, but a sample of the H.I.V. strain that he carried was preserved. Earlier this year, in the journal Nature, the evolutionary biologist Michael Worobey and his colleagues reported that they had performed a genetic analysis of the sample,

along with others from early on in the epidemic. Dugas, they concluded,

was not Patient Zero, not the first carrier of H.I.V. to America;

rather, their analysis revealed that the virus arrived in New York City

from the Caribbean in the nineteen-seventies, a decade before Dugas

entered our country. They trace the mistake to a simple typo: as

investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were

attempting to track the AIDS outbreak, they labelled

Dugas Patient O, where “O” indicated that he resided “outside of

California.” Finally, science has corrected the record. This serves as a

cautionary tale for medical professionals, journalists, and laypeople

alike to resist clinical indictments based on hearsay, if not outright

imagination.

Dugas succumbed to an AIDS-related cancer in 1984, but a sample of the H.I.V. strain that he carried was preserved. Earlier this year, in the journal Nature, the evolutionary biologist Michael Worobey and his colleagues reported that they had performed a genetic analysis of the sample,

along with others from early on in the epidemic. Dugas, they concluded,

was not Patient Zero, not the first carrier of H.I.V. to America;

rather, their analysis revealed that the virus arrived in New York City

from the Caribbean in the nineteen-seventies, a decade before Dugas

entered our country. They trace the mistake to a simple typo: as

investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were

attempting to track the AIDS outbreak, they labelled

Dugas Patient O, where “O” indicated that he resided “outside of

California.” Finally, science has corrected the record. This serves as a

cautionary tale for medical professionals, journalists, and laypeople

alike to resist clinical indictments based on hearsay, if not outright

imagination.Your Bubbe Is Not Always Right

Everyone

loves a folk remedy. For more than a century, grandmothers and

physicians have prescribed cranberry juice as a cure for urinary-tract

infections, which are caused by bacteria in the bladder and urethra.

Like many tenacious folk remedies, this one appears to have some basis

in science. Quinic acid, which is present in cranberries, is metabolized

by the body into hippuric acid, a substance that in very high

concentrations is toxic to E. coli, the pathogen most commonly

to blame for U.T.I.s. Researchers have also found that lectins,

carbohydrate-rich molecules in cranberries, can (in a test tube, at

least) prevent E. coli from attaching to the cells that line the urinary tract.

Alas, the wisdom of the bubbe often collapses under rigorous testing. Last month, researchers at the Yale School of Medicine published the results of

an investigation into the cranberry remedy. They performed their study

in nursing homes, where U.T.I.s are common, giving a hundred and

eighty-five women aged sixty-five and older either cranberry capsules or

a placebo. (Neither the participants nor the researchers knew what was

given to whom.) The result was striking: the two groups showed no

difference in either the number of symptomatic infections or the

presence of bacteria in the urine. Furthermore, the group given

cranberry capsules required as much antibiotic treatment as the placebo

group to eradicate the bugs.

While

other experiments have suggested the same results before, they were

conducted with small numbers of patients. The Yale study is more

definitive. Still, I am skeptical that the cranberry market will collapse.

Folk wisdom has a way of overcoming science, as Gwyneth Paltrow and

Michael Phelps have proved with their obsession over cupping, an ancient

therapy lately given new life. On the other hand, maybe bubbes aren’t

always wrong. As they say in Yiddish, “Es vet helfn vi a toytn bankes”—“It’s as helpful as cupping a corpse.”

Rethinking Prostate Cancer

For

many years, American physicians have screened their older male patients

for prostate cancer by looking at the level of a particular protein in

the blood. The protein, called prostate-specific antigen (P.S.A.), can

indicate the presence of a tumor long before any symptoms materialize.

Recently, though, there has been a movement within the medical community

against P.S.A. testing; since prostate cancers typically grow very

slowly and rarely cause discomfort, the thinking goes, early screening

may not be all that useful. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force,

based on data from two large clinical trials, currently recommends

against routine screening, but other expert groups (using the same

evidence) have countered that men should be allowed to choose for

themselves.

Now the dispute has become even more fraught. In October, The New England Journal of Medicine published a study by

a group of British researchers that examined three classes of

prostate-cancer patients: those who had received surgery, those who had

received radiation therapy, and those whose disease had been carefully

monitored without intervention. After ten years, there was no difference

in survival rates among the three groups. Active treatment does not

change the over-all risk of death, and this was the headline in most

news reports. But largely overlooked in the press was that metastases,

meaning spread of the cancer beyond the prostate gland to tissues in the

pelvis and to bone, occurred three times more frequently in those being

monitored than in those who received surgery or radiation. Not

surprisingly, the cancer also progressed more quickly in these men.

In an editorial that

accompanied the study, Anthony D’Amico, a radiation oncologist at

Boston’s Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, argued that men should be

informed of the risk of metastasis and of its consequences, particularly

pelvic tumors and bone pain and fracture. D’Amico advises that men who

wish to avoid metastases should consider monitoring, rather than surgery

or radiation, only if their life expectancy is less than a decade.

Having cared for many men with prostate cancer that metastasized—an

incurable situation often marked by severe suffering—I strongly concur.

A Knife in the Back, Again

As

we age, the wear and tear on our joints can not only erode cartilage

but also cause bone to overgrow. Bone spurs are familiar in the feet and

knees, but they can occur in the spine as well, narrowing both the

central canal through which nerves pass and the small openings, called

foramina, where they exit. This narrowing is termed spinal stenosis, and

has characteristic symptoms: walking exacerbates the condition, causing

pain and muscle weakness, and rest makes it subside. Physical therapy

and anti-inflammatory agents can afford some relief, but many patients

ultimately require surgery, particularly if there is a chance that

muscle strength will be permanently lost.

Spinal

surgery is lucrative. A simple laminectomy, in which the back portions

of a couple vertebrae are removed in order to widen the canal, might

cost five or seven thousand dollars. But a popular addition to

laminectomy is a so-called fusion, in which adjoining vertebrae are

connected with titanium hardware, keeping them aligned and the spine

stable. This raises the price to fifteen thousand or twenty thousand

dollars, or more. Perhaps as a result, there has been a sharp rise in

the number of fusion surgeries in the United States: between 2002 and

2007 alone, the increase was fifteen-fold.

Fortunately, we now have data that may temper the drive for fusion surgery. In April, Swedish scientists published the results of

an inquiry into spinal-stenosis treatments, examining nearly two

hundred and fifty patients who had been randomly assigned to undergo

laminectomy alone or added fusion. After two years, both groups of

patients functioned equally well. Those who had received fusions, of

course, had spent more time in the hospital, experienced more

complications, and cost the Swedish health-care system a good deal more

money.

I have never suffered from

spinal stenosis, but more than a decade ago I underwent fusion surgery

for back pain and “concern” over spinal instability. As I noted in an

essay for the magazine called “A Knife in the Back,”

the procedure left me in more pain than before and limited my

functioning for years. In spine surgery, it seems, less may not be more,

but it can be equivalent.

Under the Gun

We

usually think of public-health measures as targeting the pathogens and

substances that cause our bodies harm—viruses, tainted drinking water,

addictive drugs like oxycodone and heroin. But one of the leading

threats to the health of the nation is access to firearms. For the past

twenty years, the C.D.C. has largely refrained from investigating gun

deaths as a public-health issue; although the agency tracks them, it was

forbidden by Congress, in 1996, from spending money to “advocate or

promote gun control,” and the effects of that measure have lingered.

(“I’m sorry, but a gun is not a disease,” the former House Speaker John

Boehner said last year.)

Fortunately, Australians seem to have no such delusions. In July, researchers at the University of Sydney published an analysis of

how a major reform law from 1996, which banned semiautomatic rifles and

pump-action shotguns and created an extensive gun-buyback program, has

affected firearm fatalities in the country. In the seventeen years

before the law was passed, thirteen mass shootings occurred in

Australia; since 1996, there have been none. In addition, the authors

note, there was a two-thirds decline in the over-all rate of firearm

deaths.

Beyond these compelling

numbers, there are lessons to be learned in the political arena. The

Australian legislation was a direct reaction to a mass shooting in Port

Arthur, Tasmania, in which thirty-five people were murdered and at least

eighteen were wounded by an assailant with a semiautomatic rifle. The

public outcry brought together Australia’s political parties from the

right and left; indeed, it was a conservative Prime Minister, John

Howard, who spearheaded the reform. Shamefully, nothing of the sort

followed the killing of twenty children and six adults in Newtown,

Connecticut, in 2012, or the attack on the Orlando, Florida, night club

this June that resulted in the deaths of forty-nine victims. The recent

data from Australia should remind us that our politicians’ failure to

keep high-powered weapons out of public circulation is utterly

inexcusable.

Jerome Groopman, a staff writer since 1998, writes primarily about medicine and biology.

En 1516, c'est au tour des Ottomans de s'y implanter. Sous leur tutelle, Vénitiens, Français et Anglais s'invitent dans ce lieu commercial stratégique. Ces nations finissent par s'en désintéresser au profit de leurs colonies, marquant ainsi le déclin de la ville de nouveau fragilisée par un important séisme en 1822.

En 1516, c'est au tour des Ottomans de s'y implanter. Sous leur tutelle, Vénitiens, Français et Anglais s'invitent dans ce lieu commercial stratégique. Ces nations finissent par s'en désintéresser au profit de leurs colonies, marquant ainsi le déclin de la ville de nouveau fragilisée par un important séisme en 1822.

Au cœur de la ville se dresse l'ancien tell de la cité néo-hittite (Xe s. av. J.-C.).

Au cœur de la ville se dresse l'ancien tell de la cité néo-hittite (Xe s. av. J.-C.).

Depuis le XIIe siècle, sur plus de 10 kilomètres d'allées en contrebas de la citadelle, les petites boutiques du vieux marché s'alignent suivant leur spécialité dans un désordre très organisé.

Depuis le XIIe siècle, sur plus de 10 kilomètres d'allées en contrebas de la citadelle, les petites boutiques du vieux marché s'alignent suivant leur spécialité dans un désordre très organisé. Au IX s., les Qarmates, membres d'une secte chiite, organisèrent ces ensembles en veillant à la qualité des produits et créant des taxes.

Au IX s., les Qarmates, membres d'une secte chiite, organisèrent ces ensembles en veillant à la qualité des produits et créant des taxes.

Toujours en activité, les savonneries font la réputation d'Alep depuis l'époque ayyoubide, au XIIe s. À la veille de la guerre civile, elles produisaient encore 25 000 pièces par jour (6 tonnes).

Toujours en activité, les savonneries font la réputation d'Alep depuis l'époque ayyoubide, au XIIe s. À la veille de la guerre civile, elles produisaient encore 25 000 pièces par jour (6 tonnes). Bâtiment moderne sans charme, le musée archéologique d'Alep a pourtant une importance considérable : il renferme les trésors archéologiques de la région, en particulier des villes de Mari (XXXe s. av. J.-C.), d'Ebla (XXIV s. av. J.-C.) et d'Ougarit (XIIIe s. av. J.-C.) qui sont aux sources de la civilisation.

Bâtiment moderne sans charme, le musée archéologique d'Alep a pourtant une importance considérable : il renferme les trésors archéologiques de la région, en particulier des villes de Mari (XXXe s. av. J.-C.), d'Ebla (XXIV s. av. J.-C.) et d'Ougarit (XIIIe s. av. J.-C.) qui sont aux sources de la civilisation.

Celui-ci,

confronté à la menace des redoutables Lombards, ne peut plus compter

sur la protection de l'empereur de Constantinople, lequel a d'autres

soucis avec les Bulgares et les Arabes. L’empereur a, qui plus est,

décidé d’interdire les images religieuses. Or, le pape condamne

formellement l’

Celui-ci,

confronté à la menace des redoutables Lombards, ne peut plus compter

sur la protection de l'empereur de Constantinople, lequel a d'autres

soucis avec les Bulgares et les Arabes. L’empereur a, qui plus est,

décidé d’interdire les images religieuses. Or, le pape condamne

formellement l’

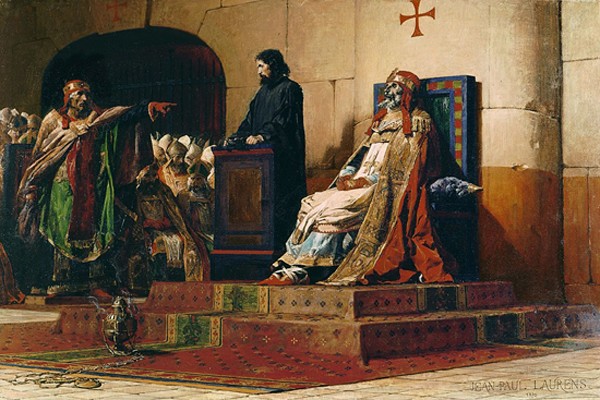

Serge III (904-911) fait la fortune du clan de Tusculum, représenté par le comte Théopylacte et son épouse Théodora. Ses opposants l'accusent d’être l’amant de leur fille Marousie.

Serge III (904-911) fait la fortune du clan de Tusculum, représenté par le comte Théopylacte et son épouse Théodora. Ses opposants l'accusent d’être l’amant de leur fille Marousie.

Il

impose sur le trône de saint Pierre son précepteur Gerbert d’Aurillac,

qui devient pape sous le nom de Sylvestre II (999-1003). Tout un

programme.

Il

impose sur le trône de saint Pierre son précepteur Gerbert d’Aurillac,

qui devient pape sous le nom de Sylvestre II (999-1003). Tout un

programme. Thomas Tanase, diplômé de l’Institut d’Études politiques de Paris, est docteur et professeur agrégé d’histoire.

Thomas Tanase, diplômé de l’Institut d’Études politiques de Paris, est docteur et professeur agrégé d’histoire.

Il

soumet les populations côtières, apparentées quant à elles aux

Mélanésiens, notamment les Sakalavas de la côte occidentale (autour du

port de Majunga), les Betsileo des plateaux méridionaux (autour de

Fianarantsoa) et les Betsimisarakas de la côte orientale (autour du

grand port de Tamatave).

Il

soumet les populations côtières, apparentées quant à elles aux

Mélanésiens, notamment les Sakalavas de la côte occidentale (autour du

port de Majunga), les Betsileo des plateaux méridionaux (autour de

Fianarantsoa) et les Betsimisarakas de la côte orientale (autour du

grand port de Tamatave).

Radama

1er, fils et successeur du grand roi, achève la soumission de l'île

avec l'appui du gouverneur britannique de l'île Maurice voisine et de

nombreux experts européens.

Radama

1er, fils et successeur du grand roi, achève la soumission de l'île

avec l'appui du gouverneur britannique de l'île Maurice voisine et de

nombreux experts européens. Radama

II, fils et successeur de la reine en 1861, rouvre les ports aux

Européens. Mais il est rapidement assassiné et sa veuve, Rasoherina,

épouse son Premier ministre, Rainilairivony, lequel va s'attribuer la

réalité du pouvoir en se remariant avec les reines suivantes, Ranavalo

II et Ranavalo III.

Radama

II, fils et successeur de la reine en 1861, rouvre les ports aux

Européens. Mais il est rapidement assassiné et sa veuve, Rasoherina,

épouse son Premier ministre, Rainilairivony, lequel va s'attribuer la

réalité du pouvoir en se remariant avec les reines suivantes, Ranavalo

II et Ranavalo III.

Philibert

Tsiranana, ancien instituteur à l'accent languedocien inimitable (il a

fait ses études à Montpellier) en devient le premier président de la

République.

Philibert

Tsiranana, ancien instituteur à l'accent languedocien inimitable (il a

fait ses études à Montpellier) en devient le premier président de la

République. Marc

Ravalomanana, un jeune chef d'entreprise élu démocratiquement à la

présidence de la République, suscite un immense espoir dans le pays.

Marc

Ravalomanana, un jeune chef d'entreprise élu démocratiquement à la

présidence de la République, suscite un immense espoir dans le pays.